New WebAssembly instrumentation

This article was originally published on the DFINITY Medium blog here by Andriy Berestovskyy, Ulan Degenbaev, Maciej Kot & Alexandru Uta.

Background

The Internet Computer (IC) is a blockchain-based platform that hosts general-purpose applications. Each application runs in a WebAssembly (Wasm) virtual machine to ensure security, safety, performance, and determinism.

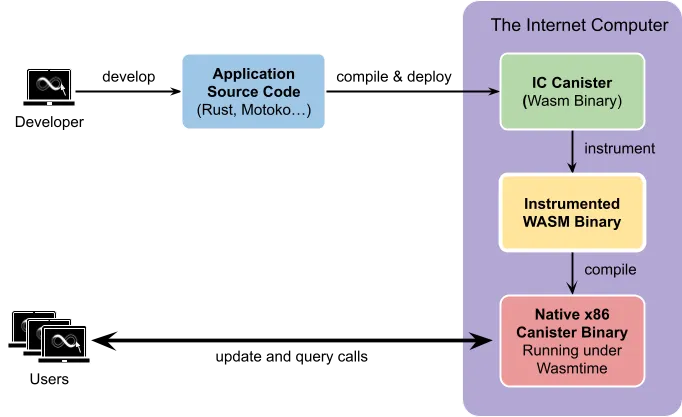

The application lifecycle on the IC includes the following steps:

Development. Using one of the supported high-level languages (Rust, Motoko, Typescript, Python…) and the corresponding Canister Development Kit library (CDK), developers implement their general-purpose applications.

Wasm compilation and deployment. The application source code is compiled and linked with the CDK library. The resulting Wasm binary is deployed on the IC, and is called a canister.

Once deployed, the canister is ready to receive messages from users and other canisters. Prior to the very first message execution, the newly deployed Wasm binary must undergo two more transformations:

Instrumentation. The Internet Computer inserts system-level code into the Wasm binary to count the number of executed instructions.

Native compilation. Finally, the instrumented Wasm binary is being compiled into native x86 code to achieve near-native application performance.

More details can be found in the WebAssembly on the Internet Computer article.

Now, let’s dive into the instrumentation process.

The Internet Computer instruments Wasm binaries by injecting tiny snippets of code to count the number of executed instructions. This is needed to ensure that canister execution terminates and the canister is fairly charged. The number of executed instructions is also known as the program counter on other blockchains.

As every single executed instruction must be correctly counted, the instrumentation step is critical for the performance of the canisters and the Internet Computer block rate consistency.

The old Wasm instrumentation algorithm works well, but is inefficient for certain kinds of applications such as language interpreters. The new Wasm instrumentation addresses these inefficiencies and achieves an order of magnitude better performance for such applications, allowing developers to run their canisters more efficiently and cheaper.

Old instrumentation algorithm

The high-level idea of the old instrumentation algorithm is to detect “straight-line code” (basic block) and inject a few Wasm instructions to update the instruction counter at the beginning of each basic block. For reentrant blocks, such as functions and loops, the algorithm also adds a check for the out-of-instructions condition.

The old instrumentation algorithm was written before the Internet Computer Genesis, as there was no other way to measure the fuel/gas at the time.

Problematic cases

Problem 1: Over-estimation

The old instrumentation algorithm doesn’t properly handle cases when the control flow is transferred across multiple blocks. The algorithm overestimates the number of executed instructions:

Original Wasm code:

(block $b1

(block $b2

br $b1

)

[N other instructions]

)

Instrumented Wasm code:

(block $b1

instruction_counter -= N (block b2 instruction_counter -= 1 br $b1 ) [N other instructions] ) In the example above, the `br` instruction transfers control to the end of block `b1

, jumping over *N* instructions. However, the algorithm considers the *N* instructions to be part of block$b1` and accounts for them at the beginning of the block. Many languages implement switch/match expressions using nested blocks and labeled branches, which means that overestimation is probably common in practice.

The root cause of the issue is that the algorithm detected basic blocks incorrectly. The crucial property of the “straight-line code” is that the whole block must be executed unconditionally. This property does not hold as demonstrated in the example above.

Problem 2: Performance

A basic block has a single entry and a single exit point. There is a Wasm instruction called block, but the instruction does not mark neither the beginning nor the end of a “straight-line code”. The old algorithm mistakenly treated the block instruction as the beginning of the basic block.

Since the instruction_counter is stored in a global variable, updating it requires two memory accesses: one load and one store. The old instrumentation mistakenly inserts them after each block Wasm instruction. This had a huge negative impact on some applications with lots of nested block’s.

Problem 3: Scheduling and fairness

Whereas the old instrumentation treats all instructions as equal in terms of cost, the actual cost of an instruction depends on its type. For example, division is more expensive than addition, so, even if the number of Wasm instructions is the same, it would be fair to charge more for divisions.

Also, charging equally for all the instructions poses a great challenge for the Internet Computer scheduler. To be deterministic, it tries to schedule the same number of instructions per round. If most of those instructions happen to be “light”, the round finishes earlier, while if most of the instructions are “heavy”, users might observe unexpected delays.

New instrumentation algorithm

To address problem 1 (over-estimation) and problem 2 (performance) a new instrumentation algorithm was proposed for voting through the NNS. It properly detects the basic blocks (“straight-line code”) and reduces the number of memory accesses.

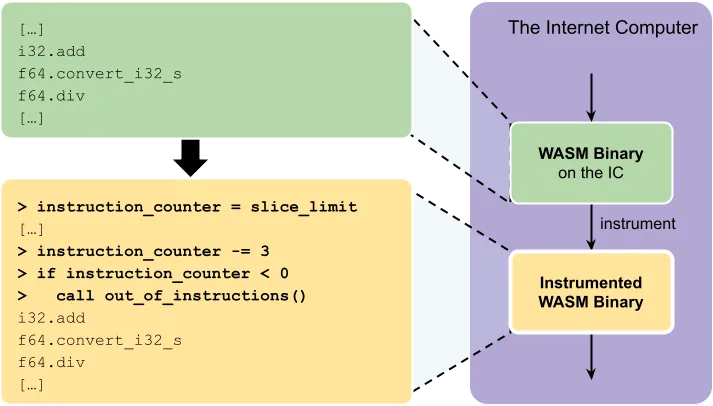

More specifically, the new instrumentation algorithm works as follows:

- Inject a new global variable:

instruction_counter = slice_limit

The counter is initialized to the execution slice limit and decreases during execution.

- At the beginning of each reentrant block (function entry or loop instruction), inject the following snippet:

instruction_counter = instruction_counter — N

if instruction_counter < 0

call out_of_instructions()

Decrement the

instruction_counterby the number of the top-level instructions in this block (not nested in other blocks) until the beginning of a next block.If the counter goes below zero, call the out_of_instructions() handler to either pause (with DTS) or terminate the execution.

At the beginning of each basic block (after each

if, else, br, br_if, br_table, end, return, unreachable, return_call, return_call_indirectinstructions), inject:instruction_counter = instruction_counter — NDecrement the

instruction_counterby the number of the top-level instructions in this block (not nested in other blocks) until the beginning of a next block.

Let’s quickly compare the old and new instrumentation algorithms. Here is the example seen previously:

Old Wasm instrumentation:

(block $b1

> instruction_counter -= N

(block $b2

> instruction_counter -= 1

br $b1

)

[N other instructions]

)

New Wasm instrumentation:

(block $b1

(block $b2

br $b1

)

> instruction_counter -= N

[N other instructions]

)

As the block instruction is neither the beginning nor the end of the “straight-line code” in the new algorithm, there are no more decrements after each block instruction, and hence the number of memory accesses for this example just halved. This might seem like a subtle difference, but many language interpreters use quite entangled match/switch statements in the very heart of the interpreting loop.

More details can be found in the instrument() function source code on github.com/dfinity/ic.

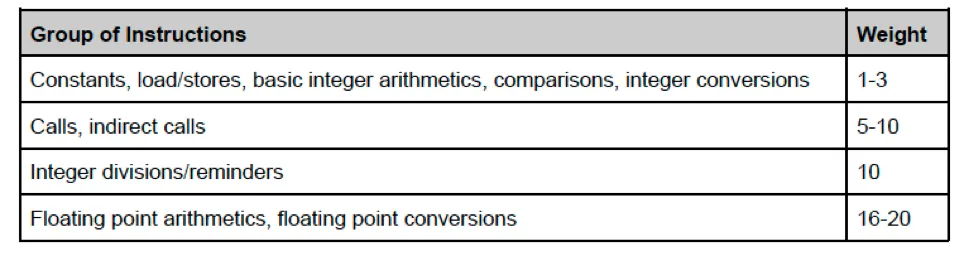

Adjustments of costs

Each Wasm instruction is assigned a “weight” as is standard practice in the blockchain world. Different instructions usually have different costs, for example varying gas costs per opcode in the EVM, as specified in the Yellow Paper. Therefore, and to address problem 3 (block rate and fairness), each Wasm instruction was assigned a new “weight” while reworking the instrumentation.

This leads to a non-uniform instruction cost model and could affect the total cycle consumption of certain workloads. To address this concern, a lot of effort was put into communicating the changes to the community, working internally with DFINITY teams, and testing.

To assign each Wasm instruction a correct weight, most instructions were benchmarked. The benchmarks provide a good estimation of the actual time the CPU spends on each Wasm instruction.

More details can be found in the wasm_instructions_bench() function on github.com/dfinity/ic.

The results for the benchmarks correlate pretty closely with the CPU instruction tablesweb, which confirms that the benchmarks make sense and pose no surprises for developers. A short summary of the costs adjustments:

More details can be found in the instruction_to_cost_new() function on github.com/dfinity/ic.

Results

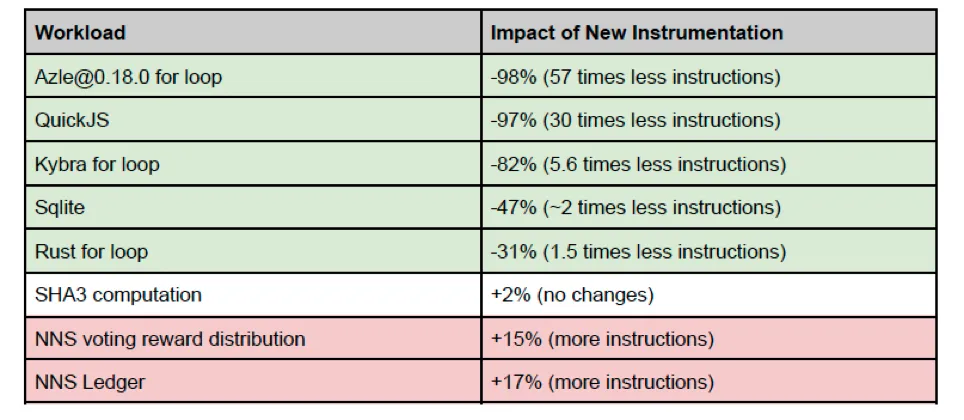

Below you can find how some applications are impacted by the new instrumentation algorithm and the new Wasm instruction weights. While this is no exhaustive list, it gives an indication of what canister developers should expect for different types of applications.

Note that an X% increase in the number of instructions does not directly translate to an X% increase in overall cost, as this does not include ingress and message execution fees.

Overall, interpreters are order of magnitude more efficient, both in terms of the number of executed instructions and the execution time. This opens the door for the new languages on the Internet Computer, like TypeScript, JavaScript and Python.

For the rest of the workloads, the results oscillate +/-20% around the old instrumentation results.This is a modest overhead, and should not surprise developers.

The new instrumentation is implemented and rolled out on all the mainnet subnets and development environments (dfx v0.15+).

Resources

Documentation: WebAssembly on ICP.

Blog post: WebAssembly on the Internet Computer.

ICP developers forum: New Wasm instrumentation

If you have questions/suggestions or just want to meet Internet Computer developers and DFINITY engineers, join the forum.dfinity.org.